As a veteran of the electoral reform campaigns in Canada, I look at Labour’s recent progress on this issue in the UK with considerable interest.

TAKING A REFERENDUM FOR GRANTED

One thing that strikes me is the way pundits are dealing with the referendum issue. There seems to me an unquestioned premise that the democratic way to proceed on electoral reform must include a referendum. Witness recent pieces to that effect, in both the Guardian and the Observer, by Owen Jones and Andrew Rawnsley, respectively. In a related article in the Daily Mail, Andrew Neil makes no presumption about a referendum, but seems to consider that the implementation of proportional representation without a referendum would be some sort of abomination.

PRECEDENTS FOR A REFERENDUM

There is indeed a precedent for a referendum on electoral reform in the UK, since a referendum is how the Alternative Vote proposal was dealt with in 2011. There are precedents also from New Zealand, which held back to back referendums in 1992 and 1993. However, nothing beats Canada for referendums on proportional representation. We’ve had seven so far —three in BC (2005, 2009 and 2018), three in Prince Edward Island (PEI) (2005, 2016, 2019) and one in Ontario (2007) —with one more in the offing in the Yukon before very long.

THE VIEW FROM CANADA

Yet in Canada, the bloom is very much off the rose on such referendums. Referendums have been no friend of electoral reform. Our experience with such referendums is that they are difficult to win and are severely biased towards the status quo. It should come as no surprise that those who advocate most strongly for the referendum option are opponents of reform.

The best result obtained in Canada was that of the 2005 referendum in British Columbia, on the heels of a citizens’ assembly, which achieved a 57.8% vote in favour of reform. However, the government had set a 60% threshold for the referendum to pass. In the 2016 referendum in Prince Edward Island, the Yes side won again, with 52.4% but the turnout was deemed insufficient.

Truth be told, referendums in Canada have been used as a way of avoiding reform by politicians preferring the status quo. Only in New Zealand has a referendum been used to overcome political resistance rather than accommodating it. When Canada held extensive hearings on electoral reform following Trudeau’s promise to make 2015 the last first-past-the-post election in Canada, the referendum option was much discussed. Remarkably 67% of expert witnesses who opined on the subject considered the referendum option to be unnecessary or ill-advised, including experts on the subject.

A BAD IDEA ON DEMOCRATIC GROUNDS!

Aside from the inherent bias of referendums in favour of the status quo are some principles-based arguments on why referendums on electoral reform are a bad idea on democratic grounds:

- Referendums are divisive, pitting one faction of the electorate against the other, as the Brexit experience has demonstrated. Yet issues like Brexit and electoral reform are issues that should be based on the maximum possible social consensus if we want such changes to be legitimate, long-lasting and widely accepted.

- Referendums are about majority rule. Yet electoral reform is about ensuring equal voting rights for all, including minorities. In referendums on electoral reform, it is very easy for the “comfortable” majority to favour the status quo at the expense of the non-at-all-comfortable minority whose vote never counts for very much.

For a referendum to be meaningful, an effective effort of public education is required. Yet in our experience, quality public education has been a woefully missing ingredient in most cases. It is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. Electoral reform is a complex issue and confusing or contradictory messaging from the pro and con sides is not helpful. From the government side, what passes for “neutrality” is technical information about the workings of different systems that are besides the point for most voters. Those who are relatively well informed tend to vote Yes. Others are likely to vote along partisan lines or to opt for the devil they know rather than one they know nothing about.

PROMISE-AND-BETRAY NO LONGER!

However, getting electoral reform without a referendum is equally challenging. If there’s another thing we have learned in Canada, it’s how difficult it can be to get promises of reform to be implemented at all. What we have instead is a promise-and-betray model of inaction: promise electoral reform when you’re sitting in third place or worse, betray that promise once elected to power. This pattern has manifested itself repeatedly in Canada, both federally and provincially.

The best known and most outrageous example of this federally was Justin Trudeau’s categorical promise that if his party was elected, 2015 would be the last first-past-the-post election in Canada. However categorical that promise may have been, Trudeau took it upon himself to abandon that promise at the end of the consultations process in 2017, saying it was his decision to make and that there was “no consensus” for reform —meaning, one can only guess, that he did not agree with the strong majority consensus by experts, citizens who showed up to testify, and the representatives of every other party.

In Quebec, this promise-and-betray pattern has manifested itself three times under three different parties: the Parti Québecois, the Liberals and most recently the Coalition Avenir Québec.

BEYOND VESTED INTERESTS

What we end up with are two very effective formulas for blocking change: breaking one’s promise outright; or less blatantly, using referendums to do the job.

The basic problem is that politicians, once they have formed government or been elected to the legislature, are in a fundamental conflict of interest when it comes to changing the electoral model that brought them to power.

This provides one reason for wishing to hold a referendum. Whatever else they might do, referendums have the advantage of giving citizens a voice where politicians are in a conflict of interest. In New Zealand, it was referendums that allowed citizens to override the resistance of the two major political parties. In the US, it’s often through citizens’ ballot initiatives that electoral reform of a mild sort can get any hearing at all.

However, referendums can be and have been used to avoid change as much as to bring it about. The question that arises is whether a better approach than referendums could not be used to gauge the will of the electorate.

A BETTER APPROACH

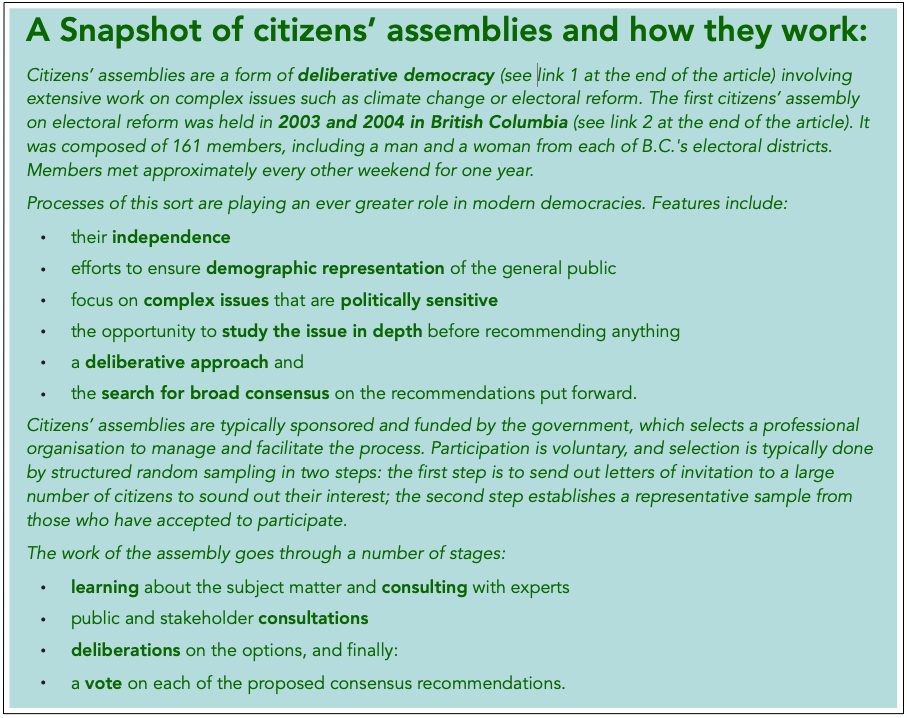

Canada has made use of other approaches in the past by mandating independent commissions or citizens’ assemblies to make recommendations. As between independent commissions and citizens’ assemblies, the latter have the advantage of being representative of the general population.

Citizens’ assemblies are now being widely used in Europe and elsewhere to address politically intractable problems, like abortion and gay rights in Ireland, or climate action in France and the UK.

Canada has had two citizens’ assemblies on electoral reform: one in B.C. (2003-2004), the other in Ontario (2007). Analysts have praised these processes for their non-partisanship and ability to reach a broad consensus. In past weeks, the Yukon government has passed legislation to also call a citizens’ assembly on electoral reform.

BOTH A CITIZENS’ ASSEMBLY AND A REFERENDUM?

Remarkably in the Yukon’s plans, is that they have judged a referendum to be desirable, nonetheless. Pairing a referendum with a citizens’ assembly might make more sense than some of the alternatives, however.

One could treat such a referendum as a “validation referendum.” The citizens’ assembly, itself a representative body of the voting public, would put forward its recommendations and rationale and a referendum would be used to determine if the general public agrees with these conclusions. This solves the public education quandary, since the rationale provided by the citizens’ assembly would be a fundamental part of what would be delivered to citizens. This was essentially the approach used in the 2005 B.C. referendum, with good success (57.8% voting Yes). The question was: “Should British Columbia change to the BC-STV electoral system as recommended by the Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform?”

CITIZENS’ ASSEMBLIES: THE KEY TO SUCCESS

Over the last four or five years, Fair Vote Canada has put citizens’ assemblies on electoral reform at the core of its electoral reform strategy in Canada. This idea is getting more and more traction and is emerging as a leading edge strategy on electoral reform.

To work properly this approach requires an acknowledgement by politicians themselves that electoral reform should be non-partisan and untethered from the conflicts of interest involved. Such an acknowledgement should come as a comfort for many politicians, giving them a way to overcome the promise-and-betray approach that has bedevilled political leaders in the past. Instead of relying on partisan advantage, the citizens’ assembly model encourages political parties and politicians to resolve their differences by handing things over to citizens themselves.

WHAT TO PUT IN A PARTY MANIFESTO?

In the face of growing voter cynicism about ever getting electoral reform out of our political leaders, the most credible promise that might be included in a party’s manifesto could well be the promise to convene a citizens’ assembly immediately after the next election. Ideally, this promise could be included by more than one party going into an election —in the UK, this could include any combination of Labour, the Liberal-Democrats, Plaid Cymru, the SNP, Reform and the Greens.

Citizens’ assemblies are never fully “binding.” However, a robust citizens’ assembly would create a high level of legitimacy for the consensus recommendations put forward and high expectations for electoral reform to be implemented. A citizens’ assembly provides a way out for political leaders whose caucus members may not all be on board with electoral reform, and helps to free them of partisan considerations that have undermined reforms in the past.

Party leaders may and should express their support for electoral reform. Why else would they convene a citizens’ assembly in the first place? However, they would be wise not to promise to unilaterally bring in a particular model of reform, an approach that could be divisive and considered illegitimate.

If there is a fear that a citizens’ assembly might propose recommendations that are not politically feasible, why not task the assembly to propose some timelines and possibly some incremental steps to enhance the political feasibility of what is being proposed?

A REFERENDUM ON ELECTORAL REFORM: GOLD STANDARD OR BOOBY TRAP?

To answer the question raised in the title of this blog, it should be clear from the above that referendums are not the gold standard. If anything, they have been used to resist rather than to promote reform.

However, the alternative approach whereby one party would win a majority after promising reform and just implement that promise once elected is no more credible. The real world does not work that way and to my knowledge, there is no case in history of a single party pursuing this sort of reform on its own.

A change of this sort requires the sort of social and political consensus that only a citizens’ assembly convened by more than one party is likely to deliver.

It’s time we set aside the notion that reform of our electoral system should depend on politicians to define for themselves how they will be elected. That is a recipe for self-serving partisanship. What we need is a recipe for building a non-partisan citizens’ consensus.

Link 1: Citizens’ assemblies: how and why they work

Link 2: British Columbia’s citizens’ assembly on Electoral Reform

Réal Lavergne is a former academic, researcher and policy analyst with a Ph.D. in Political Economy. He was President of Fair Vote Canada from 2016 to 2021 and has been involved in every Fair Vote Canada campaign over the last 10 years. Réal was a guest for a 2022 GET PR DONE! webinar: https://getprdone.org.uk/learning-from-canada/

IN PROPORTION is the blog of the cross-party/no-party campaign group GET PR DONE! (https://getprdone.org.uk/) We are campaigning to bring in a much fairer proportional representation voting system. Unless otherwise stated, each blog reflects the personal opinion of its author.

We welcome contributed blogs. Send a brief outline (maximum 75 words) to getprdone@gmail.com

Join the very active Facebook group of GET PR DONE! (+2,800 members as of May 2023.) https://www.facebook.com/groups/625143391578665/