By Ian Glenister

Ever tried to persuade someone of the need for electoral reform? Perhaps you’ve lamented the recent election results over a pint with a friend and wondered how a party with minority public backing can somehow get a whopping great majority to do what they like to the country. You might then have mused that a different, more representative kind of democracy might be fairer.

“Yeah, but we had a vote on that a few years back, and no one was interested” answered your interlocutor.

“Yeah, but we had a vote on that a few years back, and no one was interested” answered your interlocutor.

“Game over”, you might think (to use the immortal words of Nigel Farage).

The option to change the voting system in the 2011 Alternative Vote Referendum was indeed roundly defeated by a margin so huge you might think any notion of electoral reform has been expunged from the British psyche in a way we can only dream of for a certain virus.

But was it really a referendum on PR and why did it fail so badly as an exercise in changing the system?

Politics in crisis

Politics in the UK at the time was in a state of crisis. Peter Kellner, writing in ‘Democracy in Crisis’ (YouGov – [original piece removed]) said:

In today’s Britain, with universal adult franchise, we voters have the power collectively to elect politicians that we believe have the right skills and values to make decisions on our behalf. Yet only eight per cent of us think that the politicians we choose are there on merit.

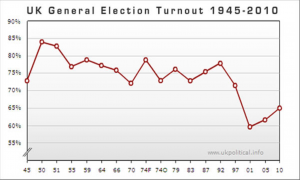

Something was clearly very wrong. Our political system was losing support. Voter turnout in GEs had plummeted to 60% in 2001 (against a 1945-1992 average of 77%) and was barely at 65% in the 2010 election that resulted in a hung parliament.

Something was clearly very wrong. Our political system was losing support. Voter turnout in GEs had plummeted to 60% in 2001 (against a 1945-1992 average of 77%) and was barely at 65% in the 2010 election that resulted in a hung parliament.

It wasn’t just the MPs’ expenses scandal that was turning off the voters. It was a feeling of powerlessness and a sense that ‘all politicians are the same, nothing ever changes’. This was combined with the growing unease that many voters felt, rightly or wrongly, as power was being signed away from Westminster and handed to Europe without them having a say in the matter.

A two horse race

Some argued that First Past The Post (FPTP) was failing British democracy. It is a system that disproportionately helps the two main parties, with each vying for the centre ground where elections are generally fought. It stifles political diversity: smaller parties are disadvantaged by this system and find it almost impossible to gain Members of Parliament, despite acquiring hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of votes.

The Lib Dems and their antecedents are continuously under-represented in the House of Commons (HoC) because their millions of votes are evenly spread among the majority of constituencies. A more proportional system, where the make-up of the HoC more accurately reflects the numbers of votes each party receives, would return dozens more Lib Dem MPs.

As well as limiting us to a two-party electoral landscape, FPTP was a system that structurally seemed to help the Tories disproportionately. In nearly all the last 20 elections, the Conservative party have polled less than 50% of the votes, and yet they have been in power for 75% of the time.

A new system, where people’s votes really counted to elect other voices in Parliament, might have very high public support. Indeed, this does seem to be the case, at least among Guardian readers, who in a 2009 poll gave a damning verdict on FPTP and came out overwhelmingly in favour of PR.

Changing the system – a ‘miserable little compromise’

In February 2010, the Labour-majority HoC voted in favour of a Referendum on AV which would have taken place had Labour won the forthcoming GE. But the 2010 GE resulted in no clear winner under FPTP and signalled the public’s dissatisfaction with the two main parties.

However, the Conservatives, as the largest party post-election, and the third largest, the Lib Dems (who achieved something of a post-war high-water mark in terms of Parliamentary seats with Kennedy and then Clegg as leaders during the Blair/Brown years) entered into coalition negotiations. For the Lib Dems, their desire for a change in the voting system would be a powerful negotiating chip.

These negotiations were protracted. Clegg, having dismissed Labour’s pre-election promise of a vote on AV as a ‘miserable little compromise’ wanted proportional representation.

But no self-respecting Tory would allow that, as it would seriously weaken the Tory stranglehold on British politics and ensure that they might never again win a majority. So as part of the ‘final offer’ for the Lib Dems, a referendum on an Alternative Vote was accepted by Clegg in return for his support for Conservative policies on cuts and tuition fees.

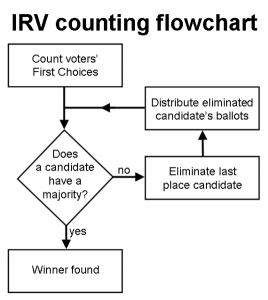

So what is AV? It is a system by which to be elected to Parliament, a candidate must achieve over 50% of the constituency vote. This gives more electoral credibility than FPTP where MPs get elected by simply getting more votes than any of their competitors individually.

FPTP often results in many MPs being returned with just 30%-40% of the vote, so in those constituencies, they are returned with a majority voting against them! Even in London’s constituencies, often with huge, immovable majorities, in 2010 only 32 out of 73 MPs were returned with majority support from their voting constituents (this doesn’t take into account the constituents who didn’t vote for whatever reason).

Under AV, voters are allowed to express a ‘second preference’ on the ballot paper. In fact, they can rank all the candidates in the order they would vote for them. In order to get past the 50% threshold, the second preference votes of the eliminated smallest parties are redistributed until a candidate achieves 50%.

Although AV had its advocates, even among Lib Dem members support was lukewarm. It was very much seen as a compromise and a means to an end – a potential future referendum on PR.

AV is clearly not a proportional system: smaller parties would still be kept out of Parliament. Caroline Lucas would probably not have won Brighton Pavilion under AV in 2010. Having polled only 31%, it is unlikely Conservative voters would have supported her as a second preference.

Nor did AV have significant support elsewhere. Very few countries use AV (also known as ‘instant runoff voting’) to decide who governs, and perhaps for good reason.

In a report commissioned by the first Blair government, AV was described as “disturbingly unpredictable” and “unacceptably unfair”. Cameron described AV as “undemocratic, obscure, unfair and crazy” and that “Britain shouldn’t have to settle for anyone’s second choice.”

A campaign with no leader

Cameron, as PM, had plenty of media time to state his views whilst Clegg, his public image tarnished by his support for Tory cuts, was kept out of the campaigning limelight and was called “the absentee father of AV” by the No campaign.

Labour were badly split too, with many prominent former ministers giving their support to the No side. The Labour left saw voting ‘No’ in the Referendum as a way to punish Clegg (for entering a coalition with the Conservatives rather than with Labour) and weaken the coalition. Miliband, though he came out in support of AV, perhaps wanted to protect his reputation in his own party (he had only been leader for a year) and wasn’t a prominent figure in the campaign.

So there wasn’t a charismatic big-hitter to act as a focal point to make the case for change. The best ‘Yes’ could do was to wheel-out a few celebrities such as Eddie Izzard. The campaigning itself was often haphazard and confusing for the public, with accusations of lying thrown at both camps:

I doubt more than one in twenty of the arguments made – either for or against AV – in this campaign have any substance to them at all. Instead, there’s been such an endless parade of misinformation, dishonesty, special pleading and scaremongering that one wonders if this country’s political and media classes can be trusted to hold any further referendums on any subject at all.

Alex Massie, The Spectator April 11, 2011 [original piece no longer available online]

The ‘No’ campaign slogan was “One person, one vote” (OPOV). An easy hook line and although disingenuous (as AV is also OPOV) much of the public fell for the No campaign making out that you could vote multiple times under AV in what would be very ‘un-British’ elections.

The public were also told that AV wouldn’t actually have changed things very much: “AV would not have transformed the result in any of the twelve postwar elections that yielded large working majorities”. What is the point of AV then? One may well ask.

However, some months before the Referendum, opinion polls seem to suggest a win for ‘Yes’ was likely. This may have spooked the well-funded No camp into overdrive. In Spring 2011 a number of ‘attack ads’ appeared in newspapers and on social media. These were in poor taste but were well-targeted showing sick babies in intensive care. “She needs a new cardiac facility, not an AV system” though controversial, was a powerful message.

However, some months before the Referendum, opinion polls seem to suggest a win for ‘Yes’ was likely. This may have spooked the well-funded No camp into overdrive. In Spring 2011 a number of ‘attack ads’ appeared in newspapers and on social media. These were in poor taste but were well-targeted showing sick babies in intensive care. “She needs a new cardiac facility, not an AV system” though controversial, was a powerful message.

At a time of financial crisis, the ‘No’ camp were able to exploit the perceived extra cost of future AV elections. Although their estimated figure of £250m is now seen as inflated and wildly inaccurate, the public then saw this kind of expenditure as frivolous.

The visceral No campaign, supported by big names and well-funded by groups such as the Tax Payers Alliance, had more focus and visibility. ‘Yes’ spent too much time talking up the technical benefits of AV whilst ignoring why a change was necessary – they missed the open goal of explaining why FPTP was so bad in the first place. This could have been a simpler message for the public to get behind.

A day of reckoning

The Referendum was set for the 5th May 2011. On this date 80% of UK local authorities also had elections and there were devolved assembly elections in Wales and Scotland. Whilst running a referendum concurrently with LA elections may seem expedient and could boost voter turnout for both, party activists concentrated their efforts on winning council seats rather than securing a vote on AV.

In the end, there was a low turnout, with just 42% of registered voters taking part. The public were far from enthused and faced with difficult, technical arguments on one side, a 2:1 majority of those who voted supported the simple ‘devil-you-know’ arguments of the No campaign. The remaining 58% were not moved to vote one way or the other.

AV was seen very much as a ‘halfway house’ – a non-solution to a problem that many people didn’t know existed. It was advocated by unpopular politicians and ‘elite’ celebrities who were easily dismissed by well-funded and plausible ‘common sense’ voices.

Had ‘Yes’ won, Clegg’s hand in the coalition would have been strengthened because the Lib Dems were predicted to win many more seats under AV in the 2015 election.

The resultant ‘No’, on the other hand, laid the ground for the subsequent Conservative victory, and a surge of the Tory Right who were able to successfully push for another referendum – on our continuing membership of the European Union.

Referenda are poor ways of deciding constitutional change in the UK, mainly because the status quo is protected by powerful forces who always appear to be more focussed and better funded. Unless all of the lessons from 2011 can be learned and a way found to overcome public apathy, there is little point in using this method to decide on changing the electoral system.

IN PROPORTION is the blog of the cross-party/no-party campaign group GET PR DONE! We are campaigning to bring in a much fairer proportional representation voting system. Unless otherwise stated, each blog reflects the personal opinion of its author.

We welcome contributed blogs. Send a brief outline (maximum 75 words) to getprdone@gmail.com