The day after BP announced record profits of £23 billion, my energy supplier tripled my monthly payments. I’m not alone, nor am I the worst off. National Energy Action estimates that when the UK Government ends the current price cap in April 2023, a shattering one in three families will face fuel poverty.

It’s true that pension funds are among the beneficiaries of the £12.5 billion shareholder dividends handed down by BP. Yet nothing can mask the bitter whiff of an energy industry so warped by market forces and world events it no longer fulfils its only real purpose—to provide efficient, affordable energy to people. Like so much of our vital infrastructure now, it functions more as a traded commodity than a human necessity. The 2001 Enron scandal is an example of where this leads.

You have to wonder if we have some structural problems in our democracies that have allowed this to happen—to the detriment of the populations they are supposed to serve. I’d argue that an electoral overhaul is long overdue.

Global Warming: The Inescapable Truth

It’s worrying enough without considering that our main sources of energy—fossil fuels like oil, coal and natural gas—are the primary cause of carbon dioxide-induced global warming.

The UK’s commitment to net zero emissions (by…erm, 2050) notwithstanding, the world is on track to reach 2.5 degrees of warming by the end of the century. Already at 1.2 degrees, we’ll likely exceed the 1.5 degrees pledged in the Paris agreement within a decade. Even 1.5 degrees will require human adaption to significant changes and is on the upper limit of tolerable. You don’t have to look very far for dire projections of what this means for life on Earth.

We’re in a fossil fuel hole: a co-dependent relationship with carbon and it’s killing us. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was a reminder, were it required, of the toxicity of the stuff. We need a rapid shift to renewable sources and away from the destructive power dynamics of dirty energy.

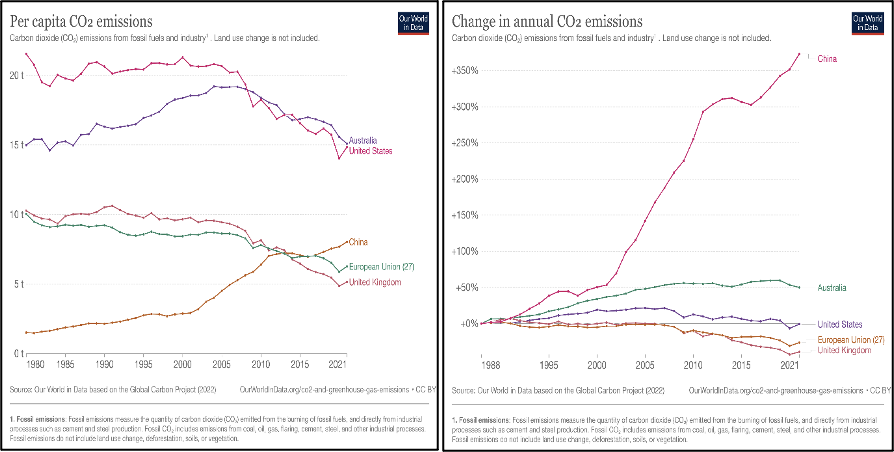

The graphs below show metric tonnes CO2 per capita and relative change in annual CO2 emissions since the mid-1980s for the UK, EU (excluding UK), US, Australia, and China.

China’s recent decades of economic growth have seen annual emissions increase almost four-fold, though per capita emissions are still way below Australia and the US.

The UK looks to be making progress, though this should be considered in the context of mass closure of coal mines through the late eighties and early nineties. The subsequent transition to gas, a lower emission fuel, is responsible for a significant amount of the reduction.

The US and Australia have made no improvement. Though per capita emissions are beginning to trend down in both countries, Australia’s annual CO2 has increased.

None of this is enough to reverse the current upward trend in global temperature. And none of it demonstrates any real commitment on the part of the major players to clean energy.

Investment in Renewables

In August 2022, a Channel 4 investigation revealed that fossil fuel companies were investing a meagre 5% of their profits in renewables like wind and solar. Bernard Looney, the chief exec of BP, recently suggested the company will ‘dial back’ on even this paltry effort. Apparently the profit margins are too small to bother with, sorry not sorry. What one fossil giant gets away with, others will copy, and it seems there’s little we can do except give them the puppy eyes.

There are whispers that energy should be a common, public resource; that it’s too vital to human survival to cast upon the whims of the markets, tossed between the super-rich like a diamond-crusted frisbee while the world simultaneously freezes and burns. The idea is gaining traction: in November 2022, two thirds of respondents to a YouGov poll supported bringing energy companies into public ownership to control prices and transition to clean energy.

Sustainable Growth?

Eternal growth on a finite planet just isn’t an option and wishing doesn’t make it so. The 2020 Living Planet report found that between 1970 and 2016, humans killed over two thirds of the world’s wildlife at an accelerating rate. In the UK, we’ve destroyed almost half of our biodiversity. Most of the loss is due to construction and agricultural expansion.

Humans rely on broad ecosystems for our survival—the food and air that keeps us alive. Crashing through it like this is suicide. That’s not a flippant comment: air pollution kills around 30,000 people a year in the UK alone. In India, it’s 1.7 million and rising.

Soon we will be forced to find a different way or face extinction. The evidence is everywhere: the floods in Pakistan; the wildfires in Australia. The process has started in the global south but it’s moving closer. It’s possible that the recent earthquakes in Turkey and Syria are climate change-related.

As the threat moves towards us, so will the people. Those who worry about migration had better buckle up as vast areas of land become uninhabitable, forcing mass movement of their populations.

Debate continues over whether it’s possible to uncouple current economic models from carbon emissions and achieve ‘sustainable growth’. Disturbingly, we’ve delayed vital action pending a conclusion to the argument. There’s no time for that. If something can spare us, must it also be required to make the rich richer?

Much of the technology we need already exists. It’s feasible and scalable with investment. We can build vast spans of solar panels, harness wind and wave, capture carbon at source and from the atmosphere. In principle, it’s even possible to convert this carbon into usable fuel. What’s stopping us?

The Democratic Chasm

An October 2022 poll found that 66% of a representative sample of the UK public supported non-violent direct action to protect the environment. Support is boosted when personal interest and environmental protection align. In September 2022, as energy costs began to bite, 77% of people in the UK supported onshore wind farm development as a means to reduce energy bills. Overall, 80% of the public think climate change is in the top three challenges we face.

Yet policy lags behind, even pulls against, this progression. The government lifted their ban of onshore wind turbines in December 2022 in response to the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Other opportunities, such as solar installation on agricultural land, remain largely untapped. Even the hard-won windfall levy on fossil fuel extractors looks limp against the backdrop of their having received more government money than they paid in tax over the previous seven years.

Undue Influence

Who makes the decisions that keep us in this hole when there’s a way out? Why are they so disconnected from our fears? In whose interests are they acting?

For a start, forty-three members of the House of Lords have significant interests in fossil fuel. In the Commons, the Conservatives received £1.3m in gifts and donations from climate sceptics and fossil fuel companies between December 2019 and October 2021. The previous Labour government’s record is also tarnished. The industry has been buying influence for decades, protecting its profits and insuring against policy shocks that would increase the cost of doing business.

Fossil fuel giant Exxon discovered the global warming effect of their products almost half a century ago, and continued to deny the truth.

Energy companies have had plenty of opportunity to build sympathy among our leaders. For those who seek political influence, the UK’s first past the post electoral system is a gift: predictable and apt to deliver absolute power in the absence of a majority popular vote.

With a couple of exceptions, there are only ever two outcomes and when change happens, you see it coming years out. Imagine the schmoozy phone calls to Labour MPs in projected safe seats right now, in anticipation of a 2024 transfer of power.

There are, we must hope, still principled members of parliament. But the question remains, what do these companies believe they are buying if it’s not influence? Like their advertising budget, if it didn’t work, they wouldn’t spend it.

Redressing the Balance

It could easily feel hopeless. However, the very cause of the deadlock could hold the key to our salvation if we flip it.

Several studies have described a correlation between proportional electoral systems (those whose results most accurately reflect the overall distribution of votes) and better environmental protections. Cohen (2010) looked at 35 democratic countries between 1997 and 2003 and found a positive association between proportional representation (PR) and faster time to ratify the Kyoto protocol. Orellana (2010) found countries with PR systems achieved 11% more CO2 emissions reduction than countries with a first past the post voting system like the UK’s.

Usually, proportional representation leads to multiple parties sharing power in coalition. In the UK, we tend to dismiss coalition governments as volatile and messy. Evidence suggests the opposite is true: they often create stability by avoiding the periodic swing between opposing policies.

By giving more parties a sustained interest, coalition fosters the long-term approach global challenges like climate change demand. Plurality of government also interrupts the access to decision makers powerful special interests currently buy. The tribalism of first past the post often prevents meaningful discussion and whipped votes are a fait accompli. Executed well, coalition encourages wider, more open debate. In times of crisis—of which recent years have delivered many—a broader base of approaches and experience can only be a good thing. It’s hard to argue it’s not a better way to do democracy.

In systems such as the single transferable vote, larger areas proportionally elect a small team of representatives rather than a single MP. This can strengthen the link between the electorate and those they bring to power. In the current UK system, if you hold opposing views to your sole representative, you effectively have no voice. And with first past the post, this could well apply to the majority of your fellow constituents: 35% of MPs earned less than half of the popular vote in the 2019 election.

At a local level, in a small team of people from different parties, you’re more likely to find one who will understand and represent your concerns in parliament. If you are among the 76% of the population who supports more local investment in renewable energy projects, or the 80% who sees the need for urgent climate action, you have a better chance of finding someone who will pay attention. You have a voice.

There’s no guarantee you’ll get everything you want because that’s not how any system of democracy works. But if enough people talk and enough politicians listen, we can achieve the change we so desperately need.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Michelle Cook lives in Worcestershire, UK and is an author of climate and thrutopian fiction.

The artwork is by the regular IN PROPORTION illustrator Glyn Goodwin.

+++++++++++++

IN PROPORTION is the blog of the cross-party/no-party campaign group GET PR DONE! (https://getprdone.org.uk/) We are campaigning to bring in a much fairer proportional representation voting system. Unless otherwise stated, each blog reflects the personal opinion of its author.

We welcome contributed blogs. Send a brief outline (maximum 75 words) to getprdone@gmail.com

Join the very active Facebook group of GET PR DONE! (+2,700 members as of January 2023.) https://www.facebook.com/groups/625143391578665/